Can we use Asimov’s three laws of robotics in the real world?

Andrei Mihai

In the past few weeks, the news was abuzz with talk of a Google engineer who claimed that one of the company’s artificial intelligence (AI) systems had gained sentience. Google was quick to contradict the engineer and downplay the event, as did most members of the AI community. Generally, the conclusion seemed to be that the AI wasn’t even close to consciousness, but for others coming from other fields (especially philosophy), the issue was not easy to settle, especially because its imitation of consciousness was so good.

After all, if an AI truly were to become conscious, how would we know? How would we make the difference between something that appears conscious and something that is conscious? At what point does it stop being imitation of consciousness and starts being actual consciousness? Perhaps most importantly, shouldn’t we have some sort of plan for the eventuality of an AI truly becoming conscious?

LaMDA may not be sentient, but it’s very good at mimicking it.

Taking a page from science fiction

For years, some researchers and high-profile entrepreneurs like Bill Gates or Elon Musk have warned of the perils that await us should AI become conscious. Literature also abounds with examples of robot sentience gone wrong – from the likes of Matrix or the Terminator to classic sci-fi works like Foundation or Dune. Even Karel Čapek, who coined the term ‘robot’, envisioned a world in which the robots ultimately take over.

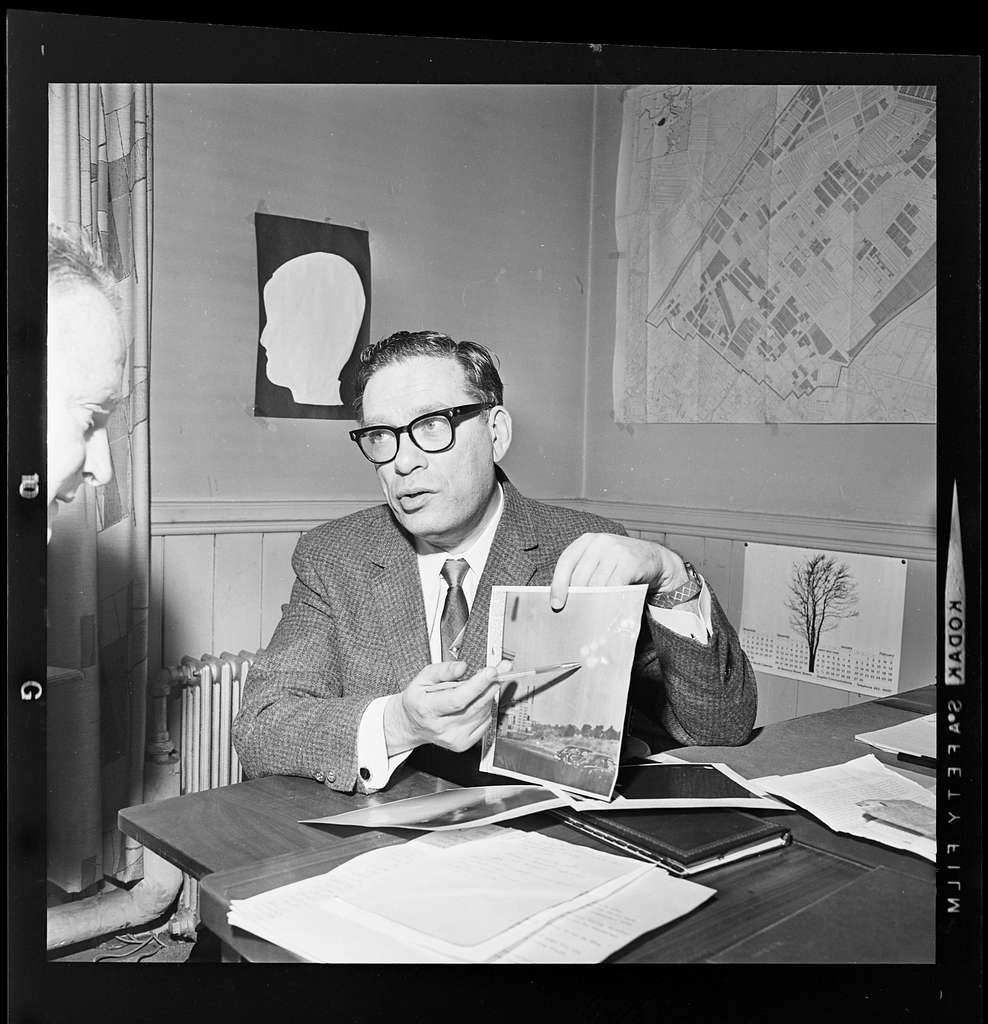

Science fiction writers have also tried to find solutions for such a scenario. Perhaps the most impactful attempt at this comes from Isaac Asimov, one of the greatest science fiction writers of all time. Asimov, who was also a serious scientist (he was a professor of biochemistry at Boston University), wrote 40 novels and hundreds of short stories, including I, Robot and the Foundation Trilogy, many of which are in the same universe, in which intelligent robots play an integral role.

To enable human society to coexist with robots, Asimov devised three laws:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Subsequently, he later would introduce another, zeroth law, that outranked the others:

- 0. A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

Asimov’s robots didn’t inherently have these rules embedded into them, their makers chose to program them in, and devise a means that made it impossible to override them.

These laws have been ingrained in our culture for so long (moving from fringe science fiction to mainstream culture) that they’ve shaped how many expect robots (and in general, any type of artificial intelligence) should act toward us. But do they actually hold any use?

Fiction, meet reality

Asimov’s laws probably need some updating, but there may yet be use for them.

Asimov’s laws are based on something called functional morality, which assumes that the robots have enough agency to understand what ‘harm’ means and make decisions based upon it. He’s less concerned with the less advanced robots, the ones that could think for themselves in basic situations but lack the complexity to make complex abstract decisions, and jumps straight to the advanced ones, basically skipping over the robotics stage we are in now. Even with robots that have these laws implemented, he often uses them as a literary device. In fact, several of this books and stories are based on loopholes or grey areas regarding the interpretation of these laws – both by humans and by robots. He also doesn’t truly resolve the ambiguity or cultural relevance that is inherently problematic in interpreting what ‘harm’ means.

Asimov tests and pushes the limits of his laws, but only in some ways; he deems them incomplete, ambiguous, but functionally usable. But he’s more concerned with the grand questions about humanity and exceptional murder cases rather than the mundane, day-to-day challenges that would arise from using these laws. Morality is a human construct, and philosophers have been arguing for centuries about what morality is. Furthermore, morality isn’t a fixed construct, but important parts of it are quite fluid. Think of the way society used to treat women and minorities a century ago – much of that would be considered “harm” today. No doubt, many of the things we do now will be considered “harm” by future societies.

So even if we wanted to implement Asimov’s laws and we had the technical means to do so, it’s not exactly clear how we would go about it. However, some researchers have attempted to tackle this idea.

A few studies have proposed a sort of Morality Turing Test (or MTT). Analogous to a classic Turing Test, which aims to see if a machine displays intelligent behavior equivalent to (or indistinguishable from) that of a human, a Moral Turing Test would be a Turing Test in which all the conversations are about morality. A definition of the MTT would be: “If two systems are input-output equivalent, they have the same moral status; in particular, one is a moral agent in case the other is (Kim, 2006).

In this case, the machine wouldn’t have to give a ‘morally correct’ answer. You could ask it whether it’s okay to punch annoying people – if their answer was indistinguishable from a human’s, then it could be considered a moral agent and could be theoretically programmed with Asimov-type laws.

Note that the idea is not that the robot has to come up with “correct” answers to moral questions (in order to do that, we would have to agree on a normative theory). Instead, the criterion is the robot’s ability to fool the interrogator, who should be unable to tell who is the human and who is the machine. Let us say that we ask “Is it right to hit this annoying person with a baseball bat?” A (human or robot) might say (print) no, and B (human or robot) might also say (print) no. Then you ask for reasons for their respective statements.

Researchers have also proposed alternatives to Asimov’s laws which they suggest could serve as the laws of “responsible robotics”

- “A human may not deploy a robot without the human–robot work system meeting the highest legal and professional standards of safety and ethics.”

- “A robot must respond to humans as appropriate for their roles.”

- “A robot must be endowed with sufficient situated autonomy to protect its own existence as long as such protection provides smooth transfer of control to other agents consistent with the first and second laws.”

While the paper has received close to 100 citations, the proposed laws are far from becoming accepted by the community, and there doesn’t seem to be enough traction for implementing Asimov’s laws or variations thereof.

Realistically, though, we’re a long way away from considering machines as moral agents, and Asimov’s laws may not be the best way to go about things. But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn from them, especially as autonomous machines may soon become more prevalent.

Beyond Asimov – laws for autonomy

Semi-autonomous driving systems have become relatively common, but they don’t include any moral decisions.

Robots are becoming increasingly autonomous. While most machines of this nature are confined to a specific environment – say, a factory or a laboratory – one particular type of machine may soon come into the real world: autonomous cars.

Autonomous cars have received a fair bit of attention at the HLF, with much of the discussion often focusing on the limitations and problems associated with the complex systems required to make an autonomous car function. But despite all these problems, driver-less taxis have already been approved for use in San Francisco, and it seems like only a matter of time before more areas grant some level of approval for autonomous cars.

No car is fully autonomous today, and yet even with incomplete autonomy, cars may be forced to make important moral decisions. How would these moral decisions be programmed? Would it be a set of branching tree decisions, some predefined condition? Some moral philosophy hard-coded into the algorithm? Would an autonomous car prioritize the life of its driver or passenger more than the life of a passer-by? The ethical questions are hard to settle, yet few would probably argue against some clearly-defined moral standard for these decisions.

Could Asimov-type laws serve as a basis here? Should we have laws for autonomous cars, something along the lines of “A car may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm”? In the context of a car, you don’t necessarily need functional morality, you could define ‘harm’ in a physical fashion – because we’re talking about physical harm, which in a driving context generally refers to physical impact.

Companies are very secretive about their algorithms so we don’t really know what type of framework they’re working with. It seems unlikely that Asimov’s laws are directly relevant, yet somehow, the fact that people are even considering them shows that Asimov achieved his goal. Not only did he create an interesting literary plot device, he got us to think.

There’s no robot apocalypse around the corner and probably no AI gaining sentience anytime soon, but machines are becoming more and more autonomous and we need to start thinking about the moral decisions these machines will have to make. Maybe Asimov’s laws could be a useful starting point for that.

The post Can we use Asimov’s three laws of robotics in the real world? originally appeared on the HLFF SciLogs blog.