Computing for social good: Shwetak Patel’s take on how computers can make society better

Andrei Mihai

The last day of the 2022 Heidelberg Laureate Forum kicked off with an engaging lecture from ACM Prize in Computing laureate Shwetak Patel, where he presented some of the ways in which computing can help make the world a better place.

Shwetak Patel at the 9th Heidelberg Laureate Forum. Image credits: Christian Flemming

Science isn’t meant to be kept in a lab. Science is meant to enhance our understanding of the world around us and make people’s lives better. This seems to also be the core belief of Shwetak Patel. Patel, who’s an academic as well as an entrepreneur, already has an impressive track record of innovations, particularly in the field of healthcare and sustainability.

“I’m very problem-driven,” the laureate says. “I look at interesting problems in the world that can be solved and I try to use computer science, maths, engineering, and computer tools to solve them. That’s what’s exciting for me.”

Patel seems firmly grounded in interdisciplinary research. It makes little sense to try to isolate yourself in different fields of research if you are trying to solve complex problems, and when you try to bring in different fields, computation also plays a key role.

“Everything where you’re creating new knowledge is a scientific endeavor, and computers are woven into everything we do about science now. All the major scientific breakthroughs, computers are instigating it – they’re no longer just simple tools.”

Computation is also no longer restricted to “traditional” computers. We carry a small computer in our pockets all the time (our smartphones), and even sensors and other devices are becoming capable of significant computation. In 2019, Patel spoke at the 7th HLF about ways of using smartphones in public health – a field he’s still very much active in. Just a couple of days ago, a paper was published by Patel’s lab, looking at how a simple smartphone camera can be used to detect blood oxygen levels down to 70%, the lowest value that should be measurable as recommended by most health agencies.

“I’m very passionate about mobile devices. It’s already showing what it can do for healthcare: People have built sensors you can plug into the phone, and the phone is already there, it’s powerful, it’s got communication opportunities. There are personalized medicine healthcare opportunities,” he said at the morning lecture.

Slide from Shwetak Patel’s presentation at the 9th HLF.

What’s in a cough

In much of his work, he uses off-the-shelf tools and sensors, and the innovation comes on the computational side. Big data, AI, and machine learning are the “secret sauce,” Patel says, noting that the most exciting developments are at the confluence of software and hardware.

For instance, in one of his projects, he looked at how tuberculosis could be detected from a cough. Tuberculosis is a very infectious lung disease that kills around 1.5 million people a year, mostly in the developing world. Detecting the disease is not always easy without the appropriate medical equipment, and such equipment is not always available.

So Patel thought maybe tuberculosis could be detected through the cough itself. Coughing is a main symptom of the disease, so it makes sense, but his idea got a lot of pushback from doctors, who argued that even the best specialists can’t identify tuberculosis from a cough. But human ears are not necessarily the best tool we have at our disposal.

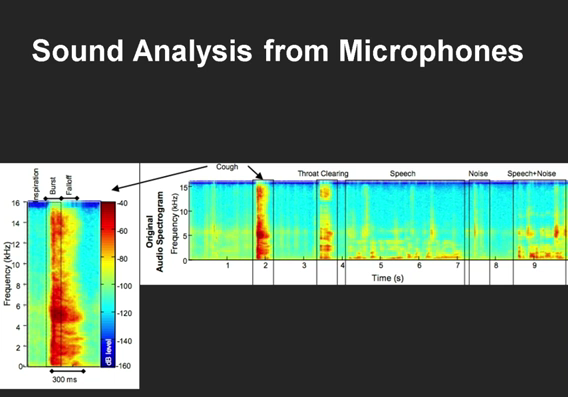

Example of cough soundwave from Shwetak Patel’s presentation at the 9th HLF.

Using conventional sound analyses, Patel and his collaborators were able to learn the mechanics and morphology of the tuberculosis-type cough and model it. Coughing only takes 0.3 seconds, “but there’s a lot happening physiologically that we can work on,” Patel says. Essentially, he was looking at the sound wave of coughing, using algorithms to find distinctive patterns that may be indicative of tuberculosis. Notably, this works for tuberculosis because the infection forms pockets in the lungs that change the audio waveform of coughing, but it doesn’t work for COVID-19.

But something else does work for COVID-19.

Presymptomatic detection

Patel mentions another project he’s been working on, which is to use commercial wearables to detect infection by analyzing patterns in things like breathing and oxygenation. Not only can this be done, he says, but it can be done even before the first notable symptoms emerge. This is a key finding because this is the period in which people tend to be most infectious, and if early quarantine or preventive treatment measures can be taken, it could make a big difference in preventing the spread and severity of respiratory infectious diseases.

Of course, these algorithms aren’t perfect, but then again neither are the antigen tests we’ve become so accustomed to. If anything, the two approaches can complement each other and improve accuracy.

The problem of inclusivity for these projects also came up. For instance, a problem with many wearable devices and sensors is that they can be less accurate for darker skin tones. Patel says he’s taking that very seriously and is working to make sure that the devices he produces work for everyone.

Patel has been working on computing applications for societal challenges for some time, and he says this approach “pulls you into different problems.” Sensing, signal processing, embedded systems, circuits, and human-computer interaction are all explored in Patel’s lab, and much of the impetus for that research comes from Patel’s students.

At the end of the lecture, the laureate took a moment to give some excellent advice to the young researchers and empower them to take their research in the direction they want to.

“Us laureates have hopefully created a framework and scaffold for you to take advantage of these tools that have been built – but it’s all on you to make the best of them. Every tool is available at your disposal, machine learning, data science… it’s an incredible time to be able to innovate.”

“When people ask me where I want to go with my research, I always say ‘wherever my students are taking me.’ You, young researchers have a lot of control over where computing research is going. I want to make sure you all are empowered.”

Patel also emphasized one of the core ideas in groundbreaking research: people’s journeys are rarely (if ever) similar. We should all find our own journeys:

“As you talk to a laureate, listen to their journey. No one journey is the right journey. You don’t have to pattern match. It’s exciting to me to talk to the laureates because everyone has a different story.”

The post Computing for social good: Shwetak Patel’s take on how computers can make society better originally appeared on the HLFF SciLogs blog.