The Internet Chronicles – Part 5 of 12: Naming and Standardizing the Web

Andrei Mihai

We take it for granted nowadays, but the internet is one of the most impactful inventions of modern times – possibly even of all time. But how did it all start? The story of the internet is a fascinating journey through the minds of visionary thinkers and relentless innovators, many of them coming from mathematics and computer science. In this 12-part series, we will dive into some of the stories and contributions of the trailblazers who laid the foundations for the interconnected world we live in today.

Previously, we explored the revolution of interactive computing and how Douglas Engelbart introduced the mouse and the concept of hypertext. But for all the tools in place, something fundamental was still missing.

The internet was growing. Computers were connecting across cities, states, and continents. Yet, finding and reaching these machines was an entirely different matter. Before you could click a link or even type a web address, you had to know exactly where you were going – by memory.

In 1968, Douglas Engelbart had foretold the future of computing with “The Mother of All Demos.” Both computers and the internet were progressing, and it was clear that big improvements were around the corner. However, accessing different networks was not the easiest thing in the world at the time.

In the beginning, every machine on the internet was assigned a numerical address, something that we would now call an IP address. Think of it like a house number but for a computer. If you wanted to send a message or connect to another computer, you needed to know its exact IP address, like 192.0.2.1. There were no search engines, no clickable links, not even user-friendly addresses like google.com. Instead, there was a single file, called HOSTS.TXT, that contained a list of every known machine on the network. Each time a new computer joined, someone had to manually update this master list and distribute it across the entire internet.

Elizabeth “Jake” Feinler wanted a better way of doing things.

Feinler had a chemistry background and had been working toward a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Purdue University. At some point, she decided to earn some money before starting work on the thesis. She became involved in a massive project to catalog all the known chemical compounds. It was a mammoth task that completely fascinated her. Feinler was intrigued by creating large data collections and would dedicate herself to this task, never returning to biochemistry.

Instead of continuing the planned Ph.D., she joined the Information Research Department at the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International) in 1960. Some of her work at the SRI would take place under Engelbart, and that is also when she started undertaking the task of organizing the internet’s directory service.

From Chemistry to the Internet

The hyperlinks that Engelbart was pioneering were useful; so was the computer mouse. However, the overarching structure of how computers and websites would be addressed had yet to be developed.

As ARPANET expanded into what would become the global internet, the flaws of the HOSTS.TXT system became overwhelming. Every time a new computer was added or an address changed, updated copies of the host file had to be manually distributed to all participating systems. Feinler quickly realized this was not sustainable. However, it was not clear what structure was sustainable and practical for this task.

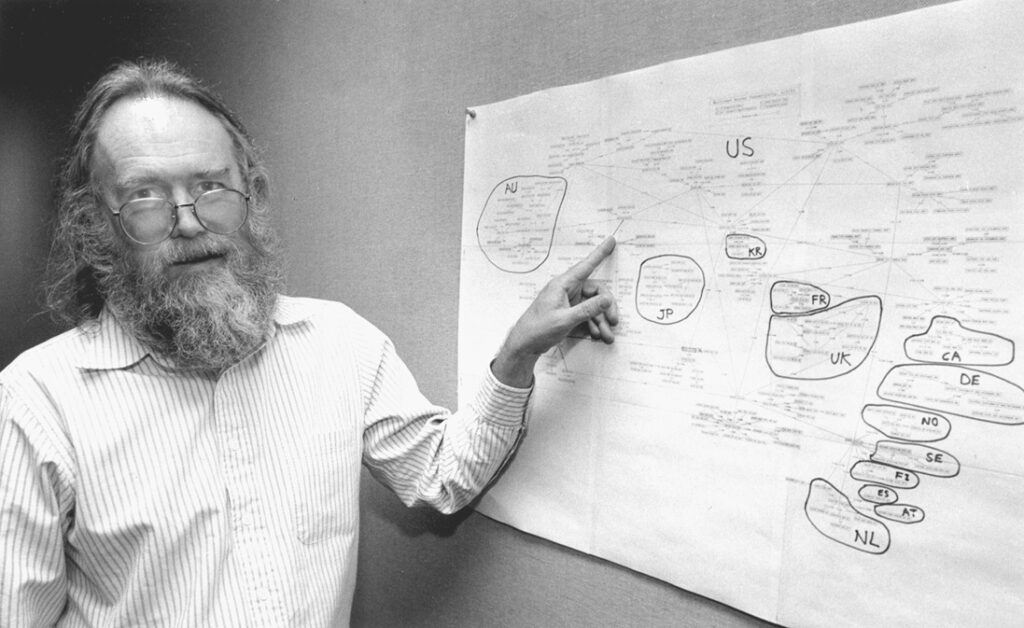

Organizing chemical molecules had taught her the importance of understanding relationships and classifications between different elements. This mindset was key to creating order in the sprawling chaos of the early networks. Engelbart also realized this. By 1972, he recruited Feinler to join his Augmentation Research Center (ARC), which operated within the US Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA). By 1974, Feinler became the principal investigator to help plan and run the new Network Information Center (NIC) for the ARPANET.

At the NIC, Elizabeth Feinler led efforts to support early internet users by offering directory services, managing user access, and distributing critical documents like Requests for Comments (RFCs). These RFCs were numbered documents that outlined technical specifications, organizational notes, and standards relevant to the Internet and networking technologies. The documents served as a platform for discussion and feedback on proposed protocols, standards, and best practices.

Working closely with other pioneers like Jon Postel and Steve Crocker, she helped formalize these documents, which would essentially become the internet’s official technical documentation. Postel, a fiercely meticulous computer scientist, would go on to become the de facto “editor of the internet” through his stewardship of the Request for Comments (RFC) series and his stewardship of core protocols. Crocker, meanwhile, had already authored RFC 1 back in 1969 as a graduate student at UCLA, laying the first brick in what would become a foundational tradition of open, collaborative protocol design. Together with Feinler, they weren’t just building a network—they were defining its rules, and doing so in a way that emphasized accessibility, decentralization, and trust.

But even with the NIC in place, the internet was still a mess of arcane addresses and manual updates. There needed to be a way to scale. A system to automate name resolution, to allow a human-friendly name – like mit.edu or gov.uk – to be translated into the numerical IP address of a machine. It was a daunting task. But Feinler was not the only one working on this task; so were several other engineers, most notably Paul Mockapetris.

DNS and WHOIS

In 1983, Mockapetris proposed the Domain Name System – or DNS. His goal was deceptively simple: create a system that could map names to IP addresses and do so in a distributed, scalable way. Instead of relying on a single HOSTS.TXT file, DNS allowed for the delegation of responsibility. Domains like .edu, .gov, and .com could be managed independently, with name servers across the world handling queries for their respective domains.

DNS was more than a clever solution; it was a conceptual leap. Like Feinler, Mockapetris envisioned a way for the internet to grow in a way that was both scalable and intuitive. Through DNS, users no longer had to remember strings of numbers. They could just type a name (something human and familiar) and the system would handle the rest.

Mockapetris wrote the initial specifications for DNS in RFC 882 and RFC 883, which have since evolved into hundreds of updates. But the foundation he envisioned became widely implemented. Every time you type a website address or click a link, you’re tapping into the infrastructure he designed. DNS made the internet usable for regular users.

During this early history, if you wanted a domain name, you would contact Feinler’s team at the NIC, where they would assign domain names (yes, they literally assigned domain names by hand). The NIC would also record ownership and contact information for the website owner. This was the early days’ catalog of the internet.

Feinler and Postel, himself one of the pioneers of the early internet standards, realized that it would be very useful to offer people a way to get direct information on who operated various websites. Thus, the WHOIS protocol was born.

While DNS mapped names to numbers, WHOIS provided metadata. It was a searchable database that let users look up who owned a domain or IP address block, when it was registered, and where they could find more information. This was not just about reducing bureaucracy. It was essential for technical coordination, network security, and the spirit of openness that defined the early net.

An Identity for the Internet

What DNS and WHOIS did – what Feinler, Postel, and Mockapetris and their colleagues oversaw – was more than solve a technical problem. They gave the internet an identity. They turned a set of wires and protocols into a knowable, searchable, navigable space. Without them, the web as we know it – full of intuitive URLs and clickable links – simply would not exist; or at the very least, it would likely have a very different form.

There is also something poetic in the way it came together: a former chemist organizing molecules; a computer scientist organizing names; engineers crafting systems that – three decades later – still support billions of users a day. The early days of the internet gathered diverse people who came with their own understanding and abilities, working together to create one of the most valuable inventions of humankind.

Still, there was something missing: a way to easily share rich, interlinked documents across different systems. The technology existed, but the right synthesis, the right vision, was still to come.

It would arrive soon, from an unexpected place: a physics laboratory in Switzerland.

In the next installment, we’ll meet the man who turned the internet into the World Wide Web and forever changed how we share knowledge.

The post The Internet Chronicles – Part 5 of 12: Naming and Standardizing the Web originally appeared on the HLFF SciLogs blog.